|

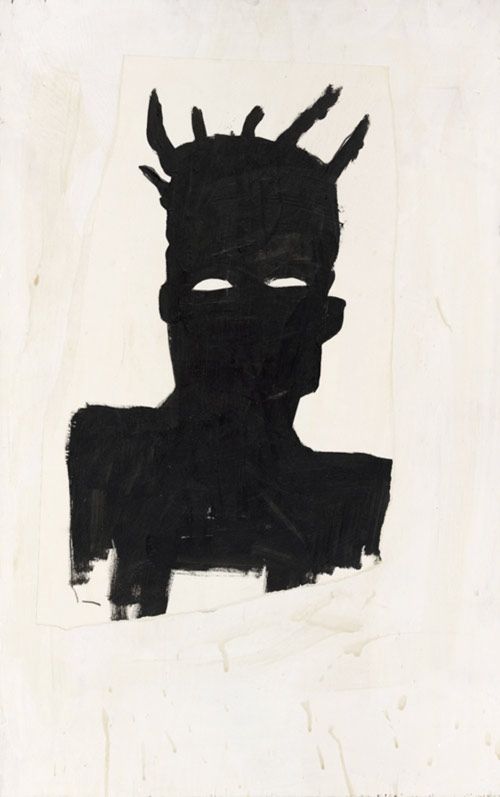

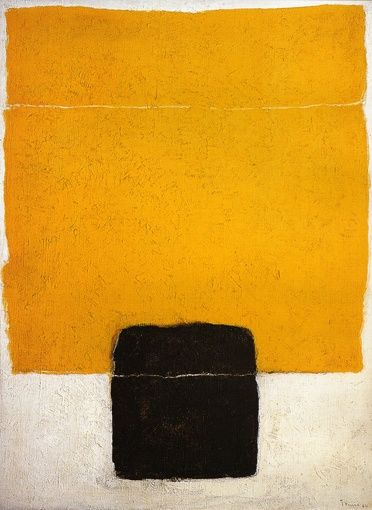

Self portrait, 1983, Jean-Michel Basquiat. “Discharging your loyal soldier will be necessary to finding authentic inner authority, or what Jeremiah promised as ‘the law written in your heart.’” One of the things I notice most in people who feel stuck in their life or self-expression is that they are paralysed by the voice in their head that tells them they "should" be doing x, y, and z. It's that voice of the inner critic, the one that tells us we're not (fill-in-the-blanks) enough. A lot of advice on how to overcome the inner critic hasn't really worked for me because it involves positioning this part of ourselves as an enemy that needs to be "silenced". To my mind, it's pretty clear that this stance will only breed more internal conflict. Here's what does work for me: allowing the inner critic to speak, and then being kind towards it, that little bit more each day. (It's an ongoing relationship with self, so expecting ourselves to nail the process overnight is unrealistic and a magnet for further criticism.) Being kind to yourself doesn't mean you'll automatically figure everything out, but it will give you a moment of breathing space. It inserts an almost imperceptible gap between the sentences in the onslaught of negative self-talk, thereby forming a crack in which to break the loop, feel some relief and begin to see the picture from a different perspective. One of my favourite authors, depth psychologist Bill Plotkin, talks about a part of ourselves called 'the loyal soldier' in his book Wild Mind: "The Loyal Soldier [is] a courageous, wise, and stubborn sub-personality that formed during our childhood and created a variety of strategies to help us survive the realities (often dysfunctional) of our families and culture. It keeps us 'safe' by making us small or limited, or by further traumatising us." The Loyal Soldier can take the shape of many guises including Rescuers, Codependents, Enablers, Pleasers, and Inner Critics. Art by Tomie Ohtake. This concept was created from a true story about a Japanese soldier who was discovered still guarding his post on a remote Pacific Island years after WWII had ended. He hadn't heard news that the war was over and he no longer needed to defend and hide. The problem with us subconsciously taking orders from our loyal soldier is that the task of protecting ourselves in this way is no longer necessary in adulthood. This position was very helpful in childhood, but we forget that childhood has finished, and not only are these roles now redundant, they're quite inhibiting at best and entirely damaging at worst.

Unfortunately, we can't just ignore the loyal soldiers or get rid of them with the snap of a finger. They're intrapsychic- they're a part of who we are. So what Plotkin suggests we do is welcome them home. Call in the troops, thank them for their work in keeping us safe over the years, but let them know their services are no longer required on the front line. They can retire; we've got this from now on. (Or, we could also reassign them to areas of our life where a certain amount of discernment is an asset- like forming healthy boundaries.) One way to do this is by writing a letter to yourself from the perspective of your inner critic. Don't censor it- let it have its say. Thank it for its perspective and protection, and then discard the paper/file afterwards (dwelling on it is probably counter-productive). Have you ever noticed during an argument with someone that if you allow their point-of-view to be truly heard and acknowledged, they actually soften? I was astounded to find that the same goes with the voice of the inner critic. Once I did this, the loyal soldier's case diffused and held less power over me. It's really quite amazing to see what we're capable of creating when we allow ourselves the permission to do so. The more we accept ourselves, the more space we have to listen to other parts of our psyches that may only be a faint whisper next to the pleading cries of the inner critic. Comments are closed.

|

Author |